Curry–Howard correspondence

In programming language theory and proof theory, the Curry–Howard correspondence (also known as the Curry–Howard isomorphism or equivalence, or the proofs-as-programs and propositions- or formulae-as-types interpretation) is the direct relationship between computer programs and proofs. It is a generalization of a syntactic analogy between systems of formal logic and computational calculi that was first discovered by the American mathematician Haskell Curry and logician William Alvin Howard.

Origin, scope, and consequences

At the very beginning, the Curry–Howard correspondence is

- the observation in 1934 by Curry that the types of the combinators could be seen as axiom-schemes for intuitionistic implicational logic,

- the observation in 1958 by Curry that a certain kind of proof system, referred to as Hilbert-style deduction systems, coincides on some fragment to the typed fragment of a standard model of computation known as combinatory logic,

- the observation in 1969 by Howard that another, more "high-level" proof system, referred to as natural deduction, can be directly interpreted in its intuitionistic version as a typed variant of the model of computation known as lambda calculus.

In other words, the Curry–Howard correspondence is the observation that two families of formalisms which had seemed unrelated—namely, the proof systems on one hand, and the models of computation on the other—were, in the two examples considered by Curry and Howard, in fact structurally the same kind of objects.

If one now abstracts on the peculiarities of this or that formalism, the immediate generalization is the following claim: a proof is a program, the formula it proves is a type for the program. Most informally, this can be seen as an analogy that states that the return type of a function (i.e., the type of values returned by a function) is analogous to a logical theorem, subject to hypotheses corresponding to the types of the argument values passed to the function; and that the program to compute that function is analogous to a proof of that theorem. This sets a form of logic programming on a rigorous foundation: proofs can be represented as programs, and especially as lambda terms, or proofs can be run.

The correspondence has been the starting point of a large spectrum of new research after its discovery, leading in particular to a new class of formal systems designed to act both as a proof system and as a typed functional programming language. This includes Martin-Löf's intuitionistic type theory and Coquand's Calculus of Constructions, two calculi in which proofs are regular objects of the discourse and in which one can state properties of proofs the same way as of any program. This field of research is usually referred to as modern type theory.

Such typed lambda calculi derived from the Curry–Howard paradigm led to software like Coq in which proofs seen as programs can be formalized, checked, and run.

A converse direction is to use a program to extract a proof, given its correctness— an area of research which is closely related to proof-carrying code. This is only feasible if the programming language the program is written for is very richly typed: the development of such type systems has been partly motivated by the wish to make the Curry–Howard correspondence practically relevant.

The Curry–Howard correspondence also raised new questions regarding the computational content of proof concepts which were not covered by the original works of Curry and Howard. In particular, classical logic has been shown to correspond to the ability to manipulate the continuation of programs and the symmetry of sequent calculus to express the duality between the two evaluation strategies known as call-by-name and call-by-value.

Speculatively, the Curry–Howard correspondence might be expected to lead to a substantial unification between mathematical logic and foundational computer science:

Hilbert-style logic and natural deduction are but two kinds of proof systems among a large family of formalisms. Alternative syntaxes include sequent calculus, proof nets, calculus of structures, etc. If one admits the Curry–Howard correspondence as the general principle that any proof system hides a model of computation, a theory of the underlying untyped computational structure of these kinds of proof system should be possible. Then, a natural question is whether something mathematically interesting can be said about these underlying computational calculi.

Conversely, combinatory logic and simply-typed lambda calculus are not the only models of computation, either. Girard's linear logic was developed from the fine analysis of the use of resources in some models of lambda calculus; can we imagine a typed version of Turing's machine that would behave as a proof system? Typed assembly languages are such an instance of "low-level" models of computation that carry types.

Because of the possibility of writing non-terminating programs, Turing-complete models of computation (such as languages with arbitrary recursive functions) must be interpreted with care, as naive application of the correspondence leads to an inconsistent logic. The best way of dealing with arbitrary computation from a logical point of view is still an actively-debated research question, but one popular approach is based on using monads to segregate provably terminating from potentially non-terminating code (an approach which also generalizes to much richer models of computation,[1] and is itself related to modal logic by a natural extension of the Curry–Howard isomorphism[ext 1]). A more radical approach, advocated by total functional programming, is to eliminate unrestricted recursion (and forgo Turing-completeness, although still retaining high computational complexity), using more controlled corecursion where non-terminating behavior is actually desired.

General formulation

In its more general formulation, the Curry–Howard correspondence is a correspondence between formal proof calculi and type systems for models of computation. In particular, it splits into two correspondences. One at the level of formulas and types that is independent of which particular proof system or model of computation is considered, and one at the level of proofs and programs which, this time, is specific to the particular choice of proof system and model of computation considered.

At the level of formulas and types, the correspondence says that implication behaves the same as a function type, conjunction as a "product" type (this may be called a tuple, a struct, a list, or some other term depending on the language), disjunction as a sum type (this type may be called a union), the false formula as the empty type and the true formula as the singleton type (whose sole member is the null object). Quantifiers correspond to dependent products or sums (as appropriate). This is summarized in the following table:

| Logic side | Programming side |

|---|---|

| universal quantification | dependent product type |

| existential quantification | dependent sum type |

| implication | function type |

| conjunction | product type |

| disjunction | sum type |

| true formula | unit type |

| false formula | bottom type |

At the level of proof systems and models of computations, the correspondence mainly shows the identity of structure, first, between some particular formulations of systems known as Hilbert-style deduction system and combinatory logic, and, secondly, between some particular formulations of systems known as natural deduction and lambda calculus.

| Logic side | Programming side |

|---|---|

| Hilbert-style deduction system | type system for combinatory logic |

| natural deduction | type system for lambda calculus |

Between the natural deduction system and the lambda calculus there there are the following correspondences:

| Logic side | Programming side |

|---|---|

| hypotheses | free variables |

| implication elimination (modus ponens) | application |

| implication introduction | abstraction |

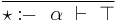

Correspondence between Hilbert-style deduction systems and combinatory logic

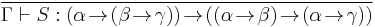

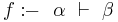

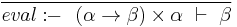

It was at the beginning a simple remark in Curry and Feys's 1958 book on combinatory logic: the simplest types for the basic combinators K and S of combinatory logic surprisingly corresponded to the respective axiom schemes α → (β → α) and (α → (β → γ)) → ((α → β) → (α → γ)) used in Hilbert-style deduction systems. For this reason, these schemes are now often called axioms K and S. Examples of programs seen as proofs in a Hilbert-style logic are given below.

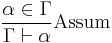

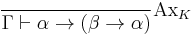

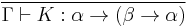

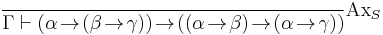

If one restricts to the implicational intuitionistic fragment, a simple way to formalize logic in Hilbert's style is as follows. Let Γ be a finite collection of formulas, considered as hypotheses. We say that δ is derivable from Γ, and we write Γ ⊢ δ, in the following cases:

- δ is an hypothesis, i.e. it is a formula of Γ,

- δ is an instance of an axiom scheme; i.e., under the most common axiom system:

- δ has the form α → (β → α), or

- δ has the form (α → (β → γ)) → ((α → β) → (α → γ)),

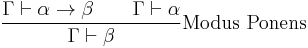

- δ follows by deduction, i.e., for some α, both α → δ and α are already derivable from Γ (this is the rule of modus ponens)

This can be formalized using inference rules, what we do in the left column of the following table.

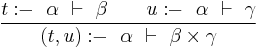

We can formulate typed combinatory logic using a similar syntax: let Γ be a finite collection of variables, annotated with their types. A term T (also annotated with its type) will depend on these variables [Γ ⊢ T:δ] when:

- T is one of the variables in Γ,

- T is a basic combinator; i.e., under the most common combinator basis:

- T is K:α → (β → α) [where α and β denote the types of its arguments], or

- T is S:(α → (β → γ)) → ((α → β) → (α → γ)),

- T is the composition of two subterms which depend on the variables in Γ.

The generation rules defined here are given in the right-column below. Curry's remark simply states that both columns are in one-to-one correspondence. The restriction of the correspondence to intuitionistic logic means that some classical tautologies, such as Peirce's law ((α → β) → α) → α, are excluded from the correspondence.

| Hilbert-style intuitionistic implicational logic | Simply-typed combinatory logic |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seen at a more abstract level, the correspondence can be restated as shown in the following table. Especially, the deduction theorem specific to Hilbert-style logic matches the process of abstraction elimination of combinatory logic.

| Logic side | Programming side |

|---|---|

| assumption | variable |

| axioms | combinators |

| modus ponens | application |

| deduction theorem | abstraction elimination |

Thanks to the correspondence, results from combinatory logic can be transferred to Hilbert-style logic and vice-versa. For instance, the notion of reduction of terms in combinatory logic can be transferred to Hilbert-style logic and it provides a way to canonically transform proofs into other proofs of the same statement. One can also transfer the notion of normal terms to a notion of normal proofs, expressing that the hypotheses of the axioms never need to be all detached (since otherwise a simplification can happen).

Conversely, the non provability in intuitionistic logic of Peirce's law can be transferred back to combinatory logic: there is no typed term of combinatory logic that is typable with type ((α → β) → α) → α.

Results on the completeness of some sets of combinators or axioms can also be transferred. For instance, the fact that the combinator X constitutes a one-point basis of (extensional) combinatory logic implies that the single axiom scheme

- (((α → (β → γ)) → ((α → β) → (α → γ))) → ((δ → (ε → δ)) → ζ)) → ζ,

which is the principal type of X, is an adequate replacement to the combination of the axiom schemes

- α → (β → α) and

- (α → (β → γ)) → ((α → β) → (α → γ)).

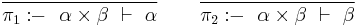

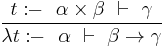

Correspondence between natural deduction and lambda calculus

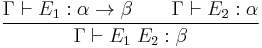

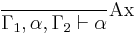

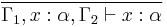

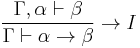

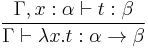

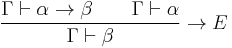

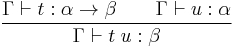

After Curry emphasized the syntactic correspondence between Hilbert-style deduction and combinatory logic, Howard made explicit in 1969 a syntactic analogy between the programs of simply-typed lambda calculus and the proofs of natural deduction. Below, the left-hand side formalizes intuitionistic implicational natural deduction as a calculus of sequents (the use of sequents is standard in discussions of the Curry-Howard isomorphism as it allows the deduction rules to be stated more cleanly) with implicit weakening and the right-hand side shows the typing rules of lambda calculus. In the left-hand side, Γ, Γ₁ and Γ₂ denote ordered sequences of formulas while in the right-hand side, they denote sequences of named formulas with all names different.

| Intuitionistic implicational natural deduction | Lambda calculus type assignment rules |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To paraphrase the correspondence, proving Γ ⊢ α means having a program that, given values with the types listed in Γ, manufactures an object of type α. An axiom corresponds to the introduction of a new variable with a new, unconstrained type, the → I rule corresponds to function abstraction and the → E rule corresponds to function application. Observe that the correspondence is not exact if the context Γ is taken to be a set of formulas as, e.g., the λ-terms λx.λy.x and λx.λy.y of type α → α → α would not be distinguished in the correspondence. Examples are given below.

Howard showed that the correspondence extends to other connectives of the logic and other constructions of simply-typed lambda calculus. Seen at an abstract level, the correspondence can then be summarized as shown in the following table. Especially, it also shows that the notion of normal forms in lambda calculus matches Prawitz's notion of normal deduction in natural deduction, from what we deduce, among others, that the algorithms for the type inhabitation problem can be turned into algorithms for deciding intuitionistic provability.

| Logic side | Programming side |

|---|---|

| axiom | variable |

| introduction rule | constructor |

| elimination rule | destructor |

| normal deduction | normal form |

| normalisation of deductions | weak normalisation |

| provability | type inhabitation problem |

| intuitionistic tautology | inhabited type |

Howard's correspondence naturally extends to other extensions of natural deduction and simply-typed lambda calculus. Here is a non exhaustive list:

- Girard-Reynolds System F as a common language for both second-order propositional logic and polymorphic lambda calculus,

- higher-order logic and Girard's System Fω

- inductive types as algebraic data type

- necessity

in modal logic and staged computation[ext 2]

in modal logic and staged computation[ext 2] - possibility

in modal logic and monadic types for effects[ext 1]

in modal logic and monadic types for effects[ext 1] - The λI calculus corresponds to relevant logic.[2]

- The local truth (∇) modality in Grothendieck topology or the equivalent "lax" modality (∘) of Benton, Bierman, and de Paiva (1998) correspond to CL-logic describing "computation types" [3]

- ...

Correspondence between classical logic and control operators

At the time of Curry, and also at the time of Howard, the proof-as-program correspondence concerned only intuitionistic logic, i.e. a logic in which, in particular, Peirce's law was not deducible. The extension of the correspondence to Peirce's law and hence to classical logic became clear from the work of Griffin on typing operators that capture the evaluation context of a given program execution so that this evaluation context can be later on reinstalled. The basic Curry–Howard-style correspondence for classical logic is given below. Note the correspondence between the double-negation translation used to map classical proofs to intuitionistic logic and the continuation-passing-style translation used to map lambda terms involving control to pure lambda terms. More particularly, call-by-name continuation-passing-style translations relates to Kolmogorov's double negation translation and call-by-value continuation-passing-style translations relates to a kind of double-negation translation due to Kuroda.

| Logic side | Programming side |

|---|---|

| Peirce's law: ((α → β) → α) → α | call-with-current-continuation |

| double-negation translation | continuation-passing-style translation |

A finer Curry–Howard correspondence exists for classical logic if one defines classical logic not by adding an axiom such as Peirce's law, but by allowing several conclusions in sequents. In the case of classical natural deduction, there exists a proofs-as-programs correspondence with the typed programs of Parigot's λμ-calculus.

Sequent calculus

A proofs-as-programs correspondence can be settled for the formalism known as Gentzen's sequent calculus but it is not a correspondence with a well-defined pre-existing model of computation as it was for Hilbert-style and natural deductions.

Sequent calculus is characterized by the presence of left introduction rules, right introduction rule and a cut rule that can be eliminated. The structure of sequent calculus relates to a calculus whose structure is close to the one of some abstract machines. The informal correspondence is as follows:

| Logic side | Programming side |

|---|---|

| cut elimination | reduction in a form of abstract machine |

| right introduction rules | constructors of code |

| left introduction rules | constructors of evaluation stacks |

| priority to right-hand side in cut-elimination | call-by-name reduction |

| priority to left-hand side in cut-elimination | call-by-value reduction |

Related proofs-as-programs correspondences

The role of de Bruijn

N. G. de Bruijn used the lambda notation for representing proofs of the theorem checker Automath, and represented propositions as "categories" of their proofs. It was in the late 1960s at the same period of time Howard wrote his manuscript; de Bruijn was likely unaware of Howard's work, and stated the correspondence independently (Sørensen & Urzyczyn [1998] 2006, pp 98–99). Some researchers tend to use the term Curry–Howard–de Bruijn correspondence in place of Curry–Howard correspondence.

BHK interpretation

The BHK interpretation interprets intuitionistic proofs as functions but it does not specify the class of functions relevant for the interpretation. If one takes lambda calculus for this class of function, then the BHK interpretation tells the same as Howard's correspondence between natural deduction and lambda calculus.

Realizability

Kleene's recursive realizability splits proofs of intuitionistic arithmetic into the pair of a recursive function and of a proof of a formula expressing that the recursive function "realizes", i.e. correctly instantiates the disjunctions and existential quantifiers of the initial formula so that the formula gets true.

Kreisel's modified realizability applies to intuitionistic higher-order predicate logic and shows that the simply-typed lambda term inductively extracted from the proof realizes the initial formula. In the case of propositional logic, it coincides with Howard's statement: the extracted lambda term is the proof itself (seen as an untyped lambda term) and the realizability statement is a paraphrase of the fact that the extracted lambda term has the type that the formula means (seen as a type).

Gödel's dialectica interpretation realizes (an extension of) intuitionistic arithmetic with computable functions. The connection with lambda calculus is unclear, even in the case of natural deduction.

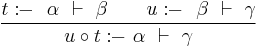

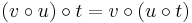

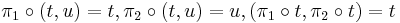

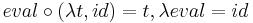

Curry–Howard–Lambek correspondence

Joachim Lambek showed in the early 1970s that the proofs of intuitionistic propositional logic and the combinators of typed combinatory logic share a common equational theory which is the one of cartesian closed categories. The expression Curry–Howard–Lambek correspondence is now used by some people to refer to the three way isomorphism between intuitionistic logic, typed lambda calculus and cartesian closed categories, with objects being interpreted as types or propositions and morphisms as terms or proofs. The correspondence works at the equational level and is not the expression of a syntactic identity of structures as it is the case for each of Curry's and Howard's correspondences: i.e. the structure of a well-defined morphism in a cartesian-closed category is not comparable to the structure of a proof of the corresponding judgment in either Hilbert-style logic or natural deduction. To clarify this distinction, the underlying syntactic structure of cartesian closed categories is rephrased below.

Objects (types) are defined by

is an object

is an object- if

and

and  are objects then

are objects then  and

and  are objects.

are objects.

Morphisms (terms) are defined by

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are morphisms

are morphisms- if

is a morphism,

is a morphism,  is a morphism

is a morphism - if

and

and  are morphisms,

are morphisms,  and

and  are morphisms.

are morphisms.

Well-defined morphisms (typed terms) are defined by the following (typing) rules (in which the usual categorical morphism notation  is replaced with sequent calculus notation

is replaced with sequent calculus notation  ):

):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finally, the equations of the category are

,

,  ,

,

Now, there exists  such that

such that  iff

iff  is provable in implicational intuitionistic logic,.

is provable in implicational intuitionistic logic,.

Examples

Thanks to the Curry–Howard correspondence, a typed expression whose type corresponds to a logical formula is analogous to a proof of that formula. Here are examples.

The identity combinator seen as a proof of α → α in Hilbert-style logic

As a simple example, we construct a proof of the theorem α → α. In lambda calculus, this is the type of the identity function I = λx.x and in combinatory logic, the identity function is obtained by applying S twice to K. That is, we have I = ((S K) K). As a description of a proof, this says that to prove α → α, we can proceed as follows:

- instantiate the second axiom scheme with the formulas α, β → α and α, so that to obtain a proof of (α → ((β → α) → α)) → ((α → (β → α)) → (α → α)),

- instantiate the first axiom scheme once with α and β → α, so that to obtain a proof of α → ((β → α) → α),

- instantiate the first axiom scheme a second time with α and β, so that to obtain a proof of α → (β → α),

- apply modus ponens twice so that to obtain a proof of α → α

In general, the procedure is that whenever the program contains an application of the form (P Q), we should first prove theorems corresponding to the types of P and Q. Since P is being applied to Q, the type of P must have the form α → β and the type of Q must have the form α for some α and β. We can then detach the conclusion, β, via the modus ponens rule.

The composition combinator seen as a proof of (β → α) → (γ → β) → γ → α in Hilbert-style logic

As a more complicated example, let's look at the theorem that corresponds to the B function. The type of B is (β → α) → (γ → β) → γ → α. B is equivalent to (S (K S) K). This is our roadmap for the proof of the theorem (β → α) → (γ → β) → γ → α.

First we need to construct (K S). We make the antecedent of the K axiom look like the S axiom by setting α equal to (α → β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ, and β equal to δ (to avoid variable collisions):

- K : α → β → α

- K[α = (α → β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ, β=δ] : ((α → β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ) → δ → (α → β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ

Since the antecedent here is just S, we can detach the consequent using Modus Ponens:

- K S : δ → (α → β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ

This is the theorem that corresponds to the type of (K S). We now apply S to this expression. Taking S

- S : (α → β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ

we put α = δ, β = α → β → γ, and γ = (α → β) → α → γ, yielding

- S[α = δ, β = α → β → γ, γ = (α → β) → α → γ] : (δ → (α → β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ) → (δ → (α → β → γ)) → δ → (α → β) → α → γ

and we then detach the consequent:

- S (K S) : (δ → α → β → γ) → δ → (α → β) → α → γ

This is the formula for the type of (S (K S)). A special case of this theorem has δ = (β → γ):

- S (K S)[δ = β → γ] : ((β → γ) → α → β → γ) → (β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ

We need to apply this last formula to K. Again, we specialize K, this time by replacing α with (β → γ) and β with α:

- K : α → β → α

- K[α = β → γ, β = α] : (β → γ) → α → (β → γ)

This is the same as the antecedent of the prior formula, so we detach the consequent:

- S (K S) K : (β → γ) → (α → β) → α → γ

Switching the names of the variables α and γ gives us

- (β → α) → (γ → β) → γ → α

which was what we had to prove.

The normal proof of (β → α) → (γ → β) → γ → α in natural deduction seen as a λ-term

We give below a proof of (β → α) → (γ → β) → γ → α in natural deduction and show how it can be interpreted as the λ-expression λ a. λb. λ g.(a (b g)) of type (β → α) → (γ → β) → γ → α.

a:β → α, b:γ → β, g:γ ⊢ b : γ → β a:β → α, b:γ → β, g:γ ⊢ g : γ

——————————————————————————————————— ————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

a:β → α, b:γ → β, g:γ ⊢ a : β → α a:β → α, b:γ → β, g:γ ⊢ b g : β

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

a:β → α, b:γ → β, g:γ ⊢ a (b g) : α

————————————————————————————————————

a:β → α, b:γ → β ⊢ λ g. a (b g) : γ → α

————————————————————————————————————————

a:β → α ⊢ λ b. λ g. a (b g) : (γ → β) -> γ → α

————————————————————————————————————

⊢ λ a. λ b. λ g. a (b g) : (β → α) -> (γ → β) -> γ → α

Other applications

Recently, the isomorphism has been proposed as a way to define search space partition in Genetic Programming.[4] The method indexes sets of genotypes (the program trees evolved by the GP system) by their Curry–Howard isomorphic proof (referred to as a species).

References

- ^ Moggi, Eugenio (1991), "Notions of Computation and Monads", Information and Computation 93 (1), http://www.disi.unige.it/person/MoggiE/ftp/ic91.pdf

- ^ Sørenson, Morten; Urzyczyn, Paweł, Lectures on the Curry-Howard Isomorphism, http://folli.loria.fr/cds/1999/library/pdf/curry-howard.pdf

- ^ Goldblatt, "7.6 Grothendieck Topology as Intuitionistic Modality", Mathematical Modal Logic: A Model of its Evolution, pp. 76–81, http://homepages.mcs.vuw.ac.nz/~rob/papers/modalhist.pdf. The "lax" modality referred to is from Benton; Bierman; de Paiva (1998), "Computational types from a logical perspective", Journal of Functional Programming 8: 177–193

- ^ F. Binard and A. Felty, "Genetic programming with polymorphic types and higher-order functions." In Proceedings of the 10th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, pages 1187 1194, 2008.[1]

Seminal references

- Curry, Haskell (1934), "Functionality in Combinatory Logic", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 20, pp. 584–590.

- Curry, Haskell B.; Feys, Robert (1958), Craig, William, ed., Combinatory Logic Vol. I, Amsterdam: North-Holland, with 2 sections by William Craig, see paragraph 9E.

- De Bruijn, Nicolaas (1968), Automath, a language for mathematics, Department of Mathematics, Eindhoven University of Technology, TH-report 68-WSK-05. Reprinted in revised form, with two pages commentary, in: Automation and Reasoning, vol 2, Classical papers on computational logic 1967–1970, Springer Verlag, 1983, pp. 159–200.

- Howard, William A. (09 1980) [original paper manuscript from 1969], "The formulae-as-types notion of construction", in Seldin, Jonathan P.; Hindley, J. Roger, To H.B. Curry: Essays on Combinatory Logic, Lambda Calculus and Formalism, Boston, MA: Academic Press, pp. 479–490, ISBN 978-0-12-349050-6.

Extensions of the correspondence

- ^ a b Pfenning, Frank; Davies, Rowan (2001), "A Judgmental Reconstruction of Modal Logic", Mathematical Structures in Computer Science 11: 511–540, http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~fp/papers/mscs00.pdf

- ^ Davies, Rowan; Pfenning, Frank (2001), "A Modal Analysis of Staged Computation", Journal of the ACM 48 (3): 555–604, doi:10.1145/382780.382785, http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~fp/papers/jacm00.pdf

- Griffin, Timothy G. (1990), "The Formulae-as-Types Notion of Control", Conf. Record 17th Annual ACM Symp. on Principles of Programming Languages, POPL '90, San Francisco, CA, USA, 17–19 Jan 1990, pp. 47–57.

- Parigot, Michel (1992), "Lambda-mu-calculus: An algorithmic interpretation of classical natural deduction", Logic Programming and Automated Reasoning: International Conference LPAR '92 Proceedings, St. Petersburg, Russia, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 624, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 190–201, ISBN 978-3-540-55727-2.

- Herbelin, Hugo (1995), "A Lambda-Calculus Structure Isomorphic to Gentzen-Style Sequent Calculus Structure", in Pacholski, Leszek, Computer Science Logic, 8th International Workshop, CSL '94, Kazimierz, Poland, September 25–30, 1994, Selected Papers, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 933, Springer-Verlag, pp. 61–75, ISBN 978-3-540-60017-5.

- Gabbay, Dov; de Queiroz, Ruy (1992), "Extending the Curry–Howard interpretation to linear, relevant and other resource logics", Journal of Symbolic Logic, 57, pp. 1319–1365. (Full version of the paper presented at Logic Colloquium '90, Helsinki. Abstract in JSL 56(3):1139–1140, 1991.)

- de Queiroz, Ruy; Gabbay, Dov (1994), "Equality in Labelled Deductive Systems and the Functional Interpretation of Propositional Equality", in Dekker, Paul; Stokhof, Martin, Proceedings of the Ninth Amsterdam Colloquium, ILLC/Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam, pp. 547–565, ISBN 9074795072.

- de Queiroz, Ruy; Gabbay, Dov (1995), "The Functional Interpretation of the Existential Quantifier", Bulletin of the Interest Group in Pure and Applied Logics, 3(2–3), pp. 243–290. (Full version of a paper presented at Logic Colloquium '91, Uppsala. Abstract in JSL 58(2):753–754, 1993.)

- de Queiroz, Ruy; Gabbay, Dov (1997), "The Functional Interpretation of Modal Necessity", in de Rijke, Maarten, Advances in Intensional Logic, Applied Logic Series, 7, Springer-Verlag, pp. 61–91, ISBN 978-0-7923-4711-8.

- de Queiroz, Ruy; Gabbay, Dov (1999), "Labelled Natural Deduction", in Ohlbach, Hans-Juergen; Reyle, Uwe, Logic, Language and Reasoning. Essays in Honor of Dov Gabbay, Trends in Logic, 7, Kluwer Acad. Pub., pp. 173–250, ISBN 978-0-7923-5687-5, http://www.springer.com/philosophy/logic/book/978-0-7923-5687-5.

- de Oliveira, Anjolina; de Queiroz, Ruy (1999), "A Normalization Procedure for the Equational Fragment of Labelled Natural Deduction", Logic Journal of the Interest Group in Pure and Applied Logics, 7, Oxford Univ Press, pp. 173–215. (Full version of a paper presented at 2nd WoLLIC'95, Recife. Abstract in Journal of the Interest Group in Pure and Applied Logics 4(2):330–332, 1996.)

- Poernomo, Iman; Crossley, John; Wirsing; Martin (2005) [2005], Adapting Proofs-as-Programs: The Curry–Howard Protocol, Monographs in Computer Science, Springer, ISBN 9780387237596, concerns the adaptation of proofs-as-programs program synthesis to coarse-grain and imperative program development problems, via a method the authors call the Curry–Howard protocol. Includes a discussion of the Curry–Howard correspondence from a Computer Science perspective.

- de Queiroz, Ruy J.G.B.; de Oliveira, Anjolina (2011), "The Functional Interpretation of Direct Computations", Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science, 269, Elsevier, pp. 19–40, doi:10.1016/j.entcs.2011.03.003. (Full version of a paper presented at LSFA 2010, Natal, Brazil.)

Philosophical interpretations

- de Queiroz, Ruy J.G.B. (1994), "Normalisation and language-games", Dialectica, 48, pp. 83–123, http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119262585/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0. (Early version presented at Logic Colloquium '88, Padova. Abstract in JSL 55:425, 1990.)

- de Queiroz, Ruy J.G.B. (2001), "Meaning, function, purpose, usefulness, consequences – interconnected concepts", Logic Journal of the Interest Group in Pure and Applied Logics, 9, pp. 693–734, http://jigpal.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/9/5/693. (Early version presented at Fourteenth International Wittgenstein Symposium (Centenary Celebration) held in Kirchberg/Wechsel, August 13–20, 1989.)

- de Queiroz, Ruy J.G.B. (2008), "On reduction rules, meaning-as-use and proof-theoretic semantics", Studia Logica, 90, pp. 211–247, http://www.springerlink.com/content/27nk266126k817gq/.

Synthetic papers

- De Bruijn, Nicolaas Govert (1995), "On the roles of types in mathematics", in Groote, Philippe de, The Curry–Howard isomorphism, Cahiers du Centre de logique (Université catholique de Louvain), 8, Academia-Bruyland, pp. 27–54, ISBN 978-2-87209-363-2, http://alexandria.tue.nl/repository/freearticles/597627.pdf, the contribution of de Bruijn by himself.

- Geuvers, Herman (1995), "The Calculus of Constructions and Higher Order Logic", in Groote, Philippe de, The Curry–Howard isomorphism, Cahiers du Centre de logique (Université catholique de Louvain), 8, Academia-Bruyland, pp. 139–191, ISBN 978-2-87209-363-2, contains a synthetic introduction to the Curry–Howard correspondence.

- Gallier, Jean H. (1995), "On the Correspondence between Proofs and Lambda-Terms", in Groote, Philippe de, The Curry–Howard isomorphism, Cahiers du Centre de logique (Université catholique de Louvain), 8, Academia-Bruyland, pp. 55–138, ISBN 978-2-87209-363-2, ftp://ftp.cis.upenn.edu/pub/papers/gallier/cahiers.pdf, contains a synthetic introduction to the Curry–Howard correspondence.

Books

- edited by Ph. de Groote. (1995), De Groote, Philippe, ed., The Curry–Howard Isomorphism, Cahiers du Centre de Logique (Université catholique de Louvain), 8, Academia-Bruylant, ISBN 978-2-87209-363-2, reproduces the seminal papers of Curry-Feys and Howard, a paper by de Bruijn and a few other papers.

- Sørensen, Morten Heine; Urzyczyn, Paweł (2006) [1998], Lectures on the Curry–Howard isomorphism, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, 149, Elsevier Science, ISBN 978-0-44452-077-7, notes on proof theory and type theory, that includes a presentation of the Curry–Howard correspondence, with a focus on the formulae-as-types correspondence

- Girard, Jean-Yves (1987–90). Proof and Types. Translated by and with appendices by Lafont, Yves and Taylor, Paul. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Tracts in Theoretical Computer Science, 7), ISBN 0-521-37181-3, notes on proof theory with a presentation of the Curry–Howard correspondence.

- Thompson, Simon (1991). Type Theory and Functional Programming Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-41667-0.

- Poernomo, Iman; Crossley, John; Wirsing; Martin (2005) [2005], Adapting Proofs-as-Programs: The Curry–Howard Protocol, Monographs in Computer Science, Springer, ISBN 9780387237596, concerns the adaptation of proofs-as-programs program synthesis to coarse-grain and imperative program development problems, via a method the authors call the Curry–Howard protocol. Includes a discussion of the Curry–Howard correspondence from a Computer Science perspective.

- F. Binard and A. Felty, "Genetic programming with polymorphic types and higher-order functions." In Proceedings of the 10th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, pages 1187 1194, 2008.[2]

- de Queiroz, Ruy J.G.B.; de Oliveira, Anjolina G.; Gabbay, Dov M. (2011) [2011], The Functional Interpretation of Logical Deduction, Advances in Logic, 5, Imperial College Press / World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-4360-95-1.

Further reading

- P.T. Johnstone, 2002, Sketches of an Elephant, section D4.2 (vol 2) gives a categorical view of "what happens" in the Curry–Howard correspondence.

External links

- The Curry–Howard Correspondence in Haskell

- The Monad Reader 6: Adventures in Classical-Land: Curry–Howard in Haskell, Peirce's law.